FASCIST MUSIC

|

This demented January 2016 performance by USA Freedom Kids was an immediate legend of fascist music. The fascist nature of this performance is total, from concept (let's get some little girls to extol Dear Leader) to presentation (American flag costumes!) to setting (some batshit rally in Pensacola) to lyrics ("Enemies of freedom / Face the music / Come on boys, take 'em down!") to music (blippy and hellish) to the mere existence of this band (Florida Svengali devises scheme for his daughter to perform and gain him $$). It should be obvious that this video occupies rare air even among its fascist brethren.

The best (worst?) part of this whole thing is that the object of their jingoistic praise is now the not-unfascist President of the United States. Perfect. I only regret that I have but one post to give USA Freedom Kids.

1 Comment

David Bowie's death in January triggered many deserved tributes. He was the greatest rock star ever.

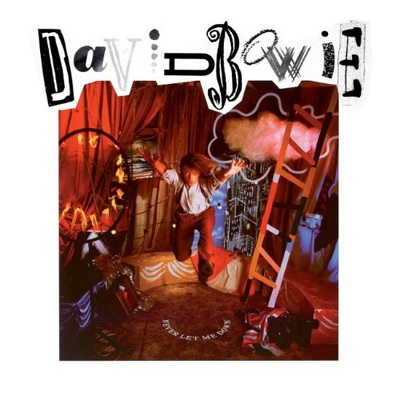

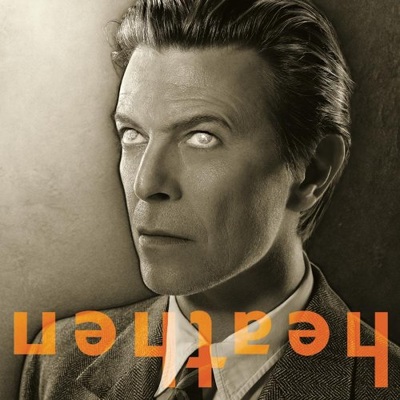

But during the 1990s (technically 1987 to 2003), he released an amazingly long and unbroken string of terrible fascist albums. It would take a perverse revisionist* -- and there were plenty in the weeks after his death -- to deny how far he fell during these years. The Cliff's Notes Bowie is this: He came on the scene in the late 1960s as a psychedelic folkie, then hit his creative stride in the early 1970s as the glam Ziggy Stardust. He soon turned to "plastic soul," the Thin White Duke persona, and mountains of cocaine. Clean by 1977, he headed to Berlin to release a trio of artsy, acclaimed albums. Then he wanted to get popular again and released a big, ominous, arena-rock album (Scary Monsters... and Super Freaks) and two popular dance-rock albums (Let's Dance and Tonight). After these commercial successes, Bowie was at a crossroads. He chose fascism.

After so many embarrassments, it was time for Bowie to finally give up, which he did. But in a happy coda, 10 years later, he released two pretty good albums, 2013's The Next Day and 2016's Blackstar. His output from 1969 to 1983 had already ensured his legacy, but these two showed he was at least capable of humor, drama, and striving -- antidotes to fascism all -- and willing to share his gifts in his waning years. *One revisionist, Jason Hartley, came up with the Advanced Genius Theory to address work exactly like Bowie's 1990s output. Per Hartley's theory, since Bowie is an acknowledged genius, it's natural that the genius present in his work would eventually exceed his audience's ability to appreciate it. The "problem," then, lies with us, not Bowie. Best known for skating rink favorite "Cotton Eye Joe," Rednex is a Swedish dance-bluegrass collective with a deeply weird American-themed aesthetic. Annika Ljungberg, Kent Olander, Arne Arstrand, Jonas Nillson, and Patrick Edenberg became Mary Joe, Bobby Sue, Ken Tacky, Billy Ray, and Mup back in 1994. They continue to trot out a surprising number of hits today in an incredibly confusing rotating troupe format, complete with several spinoffs and tributes that they formed themselves. Per Wikipedia: "On live performances and interviews, the members usually act crazy with a rough and bad behavior."

Of course, they put an obliviously Swedish spin on all their down-home cultural appropriation, starting with the fact that they pair banjos and fiddles with '90s Eurotrash dance grooves. The name, too, can only be so on-the-nose because it's coming from such a far-away place. It's the same reason there's a British band called "Texas" and a French Tex-Mex restaurant chain called "Indiana." Such a band would make no sense in Texas, and such a restaurant would make no sense in Indiana (or, frankly, anywhere). But from afar, such concepts seem exotic and worth cultural note. Cultural appropriation is generally fascist, particularly when it's tinged with cruelty toward a disadvantaged group. Really, the Rednex act is not much different from blackface. Both present cartoonish characteristics of a downtrodden minority for sport. Admittedly, Rednex targets a cultural minority group that merely has had a rough go (poor white Southerners), rather than a racial one that was systematically enslaved and oppressed for centuries (blacks). It's less offensive to parody rednecks than blacks, but it's cut from the same cloth. This is not to say Rednex was not conceived with genuine admiration as a loving tribute to Americana; it probably was. From Sweden, it might still look that way. But from America, it's a derogatory caricature of a group that has long suffered abuse, neglect, and disdain. Picking on the weak is irrevocably fascist. Though hostile nations surrounded me, I destroyed them all in the name of the LORD. -- Puff Daddy, "Forever (Intro)"

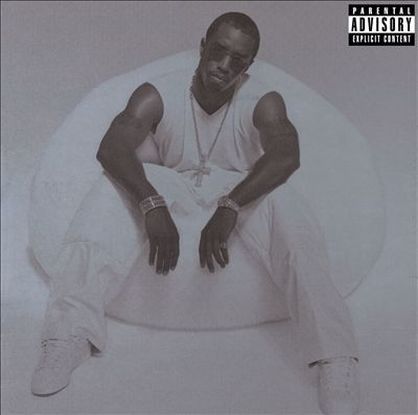

The music itself is halfway awesome but allway fascist. The holy+confrontational pose Did assumes on the cover extends to every track. It's the 2-minute choral intro from "I'll Be Missing You" in extended play. But instead of mourning Big, he's extolling himself as some kind of bedeviled Messiah -- an "Angel with a Dirty Face," to quote one track's title. Granted, this was de rigeur in late-90s rap: 2Pac started it, Ja Rule did it (of course), DMX did it. But when you aren't actually a troubled soul -- Puff was a Howard business major and record exec straight enough to date Jennifer Lopez at the time -- then your self-immolation is mass manipulation.

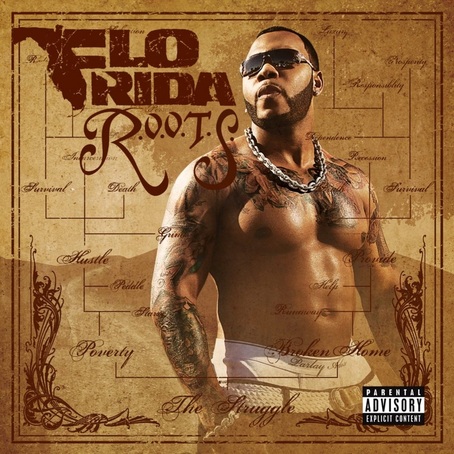

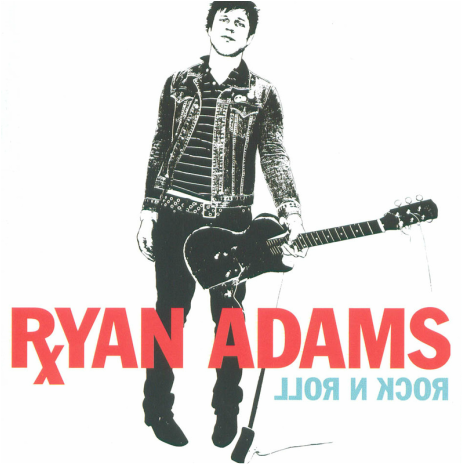

The skits take some legitimately funny premises from No Way Out, like the Mad Rapper, and blatantly appropriate them. He even steals from every other rapper ever by doing a weird impression of Scarface. Classic fascism. While the skits weren't bad, highlighted by the hilarious "ad-lib Puff," retreading everyone's favorite tropes was cynical as hell. And, of course, there's Diddy's favorite weapon, the sample. Whenever rap touches into fascist territory, it is inevitably coincident with excessive sampling, like Puff or Will Smith. "Best Friend" will knock your socks off, whether or not you know it's basically a note-for-note sample of "Sailing." He's appropriating the powerful creativity of others for his own gain; pure fascism. Finally, there's the repetitiveness. While Forever is actually kind of a good album, its droning nature -- within certain tracks, not track-to-track -- is its worst quality. Would-be hits "Do You Like It... Do You Want It," "Fake Thugs Dedication," and "Angels with Dirty Faces" are undone by repetitiveness, but the nadir -- and one of the most droning songs of all time -- is the actual hit "P.E. 2000." The song was 99% terrific, including that weird lady hypeman, but the 1% killed it. GET OFF THAT NOTE!!!!!!!!!! It's a story as old as artistic integrity: Indie rocker hits it big doing it his way and thinks he has the right to jag into something darker, label demands a more radio-friendly sound, artist balks but ultimately caves. Ryan Adams's third and Dave Matthews Band's fourth records fit the bill exactly. Adams crooned rainy-day intimacy on Heartbreaker and made a game but slightly lackluster swipe at superstardom with Gold. With Under the Table and Dreaming, Crash, and Before These Crowded Streets, DMB proved that a fervent fanbase, grassroots marketing, and great songs could overcome a lack of a genre or homerun singles. Both hit the studio in the early 2000s ready for a deep dive inward. In fact, both recorded an album's worth of despondent, spare, and uneven songs. Their respective labels were unimpressed and gently demanded that they start over: more guitars, more hooks, better work. Adams and DMB both complied. A few key differences emerge at this point, however. Adams was petulant and enraged. He thought his initial set of mopey songs, which would later be released as Love as Hell, was genius, and scoffed at his label's demand for a more rock sound. As a middle finger to his label (which, ironically, was the artist-friendly Lost Highway), he wrote and recorded a deliberately souped-up, meaningless album. Highlights (or lowlights) included a U2 parody, replete with glistening Edge-like guitar arpeggios and mock-profound lyrics ("So Alive," released as the first single); a song that sounds like an outtake from 1974 ("1974"), half an album's worth of post-grunge filler ("Burning Photographs" and "Luminol," to name two), and a song with the following lyrics: "I'm as lonely as boys / I'm as lonely as boys / I'm as lonely as monkeys taught to destroy / Anything they learn to enjoy" ("Boys"). The label released it, critics reacted with confusion or outright anger, and Adams disowned it. Ryan Adams and Dave Matthews are completely different characters, of course, and Dave's reaction matches his more earnest personality. He was just as upset as his label was that the dark, sleepy set his band recorded with producer Steve Lillywhite didn't work. So he barreled through a marathon writing and recording session with the help of pop svengali Glen Ballard, coming up with heavy, hooky songs just like Adams did. Matthews, however, wasn't joking. His band's Everyday record was just as slick, greasy, and empty as Rock N Roll, but DMB proclaimed it their best work. They cheerfully slogged through embarrassing music videos and awkwardly tried to slip dumb, offensive trifles like "I Did It" into concerts alongside their challenging and emotional repertoire. Only after fans had discarded Everyday in favor of the Lillywhite sessions did the band sheepishly and belatedly semi-disown the record.  Which is the more fascist effort? Adams consciously endeavored to create a fascist artifact of "label rock," and he certainly succeeded. But you could certainly make the argument that his record, while fascist on his face, was an arch anti-fascist commentary. Everyday doesn't get to hide within the safe cocoon of snideness; the label said jump, and Dave said how high. When you think of the way DMB repurposed the tropes of their old, organic work -- the crunchy Rolling Stone cover, the crowd-chant of "Everyday" -- you're left with the inescapable sense of dread that characterizes all the best fascist music. So while Rock N Roll hits more fascist notes in the absence of context, when you do consider context, as you must, Everyday is the more fascist record. Full disclosure: Rock N Roll is one of my favorite records by any artist ever. I like Everyday a lot, too.  Certainly, this record label's overproduced, sweet-and-salty blend of pop and rap, ostensibly fronted by a largely anonymous man called "Flo Rida," is unit-moving Big Music of fascist character. But what really fascinated me was the album title: "R.O.O.T.S.: Route of Overcoming the Struggle." Generally, and especially if you want to harken back to Alex Haley's book and "We Shall Overcome" (i.e., black Americans' struggle for civil rights), struggles are efforts toward some goal. But here, mind-bogglingly, the struggle is the thing to be overcome! It could have been "Route of Overcoming Through Struggle," which would have made more sense as a civil rights-y title. But I think Flo Rida's handlers made a conscious choice to suggest that Flo Rida was not interested in overcoming hardship through struggle; rather, their front man wanted to avoid struggle altogether. Once you have overcome struggle, what's left? Endless dancing, champagne, big DMC chains, and tighty-whiteys on blast. To advocate this vacuousness in lieu of a meaningful life, and to twist civil rights language to push this poison, is fascist. Keep the masses brainless and entertained. Flo Rida is a master of it. A counterargument might be that "The Struggle" is defined in the bizarre family tree on the album cover, and as thus defined, the term is indeed something to be overcome. But ordinary definitions matter, and when they match the civil rights references slathered all over, it's more of a "struggle" to ignore them in favor of the nonsensical diagram superimposed upon Flo Rida's gleaming torso that says the three paths from "Provide" are "Death," "Recession," and "Survival." On the surface, the inclusion of "Big Time" should be no surprise: song title, done. But this is a satirical song about a small-time guy's misguided plan to hit the titular "big time," and what he will do when he gets there. Satire is usually an anti-fascist weapon, and this song is skewering, of all things, grand ambition. So it's a legitimate question: Is this song fascist?

Yes, for two reasons. First, the narrator is meant to be an object of derision, and his delusional aspirations are understood by the savvy Gabriel and the savvy listener to be unrealistic. In other words, the concept of a small-time hustler getting a big house and bank account is presented as laughable, and that's fascist as hell. Second, if you were to give credence to the protagonist or if he were somehow to exceed expectations, his rise to the "big time," as he envisions it, would be abjectly terrifying. In his telling, he would eschew his yokel hometown friends, forsake his convictions to pledge fealty to a "big God" (probably money), and rake up material possessions, his "eyes getting bigger" all the while. Soulless success built upon the destruction of customs is a fascist fairy tale. The gold standard. The system crushes the individual.

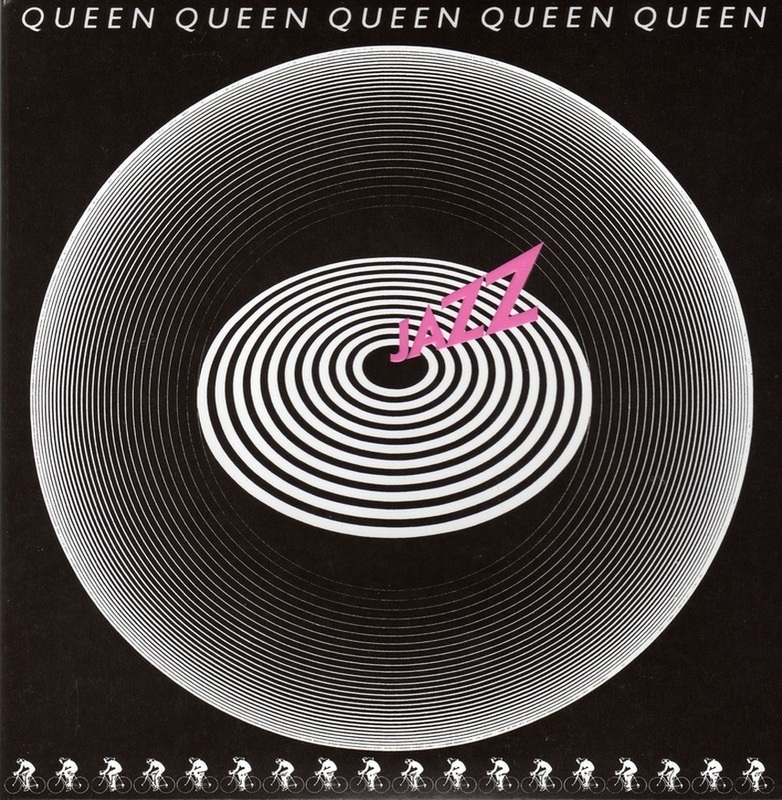

Mindless repetition of shapes, icons, and slogans. From the claustrophobia-inducing center -- where "JAZZ," in pink, the stand-in for humanity, is evidently trying to escape -- one encounters choking circles, one after another. If you are somehow able to escape the inner rings, you soon confront another, different set of rings. There is no end, no escape, as the rings gradually become infinitesimally close together. The album's title is cruelly ironic. Jazz is the freest, most organic 20th-century musical form. Its language is abstract and improvisational; its images are colorful. With its computer-generated black and white circles, this is the furthest thing from jazz. |

What is fascist music?In Dave Marsh's 1979 review of Queen's Jazz, he wrote, "Indeed, Queen may be the first truly fascist rock band." No other word so neatly expresses supremacy of the powerful and devaluation of the individual. Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed