FASCIST MUSIC

|

Generic corporate electrohipster band Capital Cities scored a minor hit in 2013 with "Safe and Sound." What do you really know about Capital Cities or "Safe and Sound?" I have an uncanny feeling that the apparent men representing themselves as Capital Cities are holograms, and the song is not so much music as a marketing pitch hatched from a fascist corporate overlord. Rudimentary research indicates that Capital Cities is presented as a duo: one clean-faced guy with a high-and-tight haircut (popular among the youth) and one James Harden-looking guy. Are we to believe that these two ciphers played all the instruments? Where is everybody else? The video provides clues: These two keep blipping and bleeping into different personae, bodies, and even eras of time. It takes tremendous effort to believe that they are not holograms. The song itself is perfectly designed to be in a car commercial or a dystopian loudspeaker. Everything is safe, sound, and taken care of. The lyrics are perfectly generic: "I could be your luck / In a tidal wave of mystery you'll still be standing next to me." Musically, it's genre-free. While catchy, it's sexless, so it doesn't fit as pop. EDM? The Capital Cities boys seem to be pushing dance in their video, but I don't buy it. And it has no pathos, or even emotion, so rock doesn't work. It's sales music. And wouldn't you know it, State Farm used the song in a commercial just this year. If you don't buy my explanation, let me ask you this: Why would human beings make this music? Don't get me wrong, I think the song is great and have probably listened to it 100 times. But it expresses nothing, in the eel-slickest, most amorphous style imaginable. Isn't music supposed to be a form of expression? What motivated High-and-Tight and James Harden to link up in Los Angeles, give themselves an aggressively fascist band name, sign to Capitol Records (really), and release corporate pitch music? There is no reasonable explanation, because that's not what happened. What happened was, a massive global conglomerate with offices in all the capital cities -- let's call it Capital Cities Corp., or CCC -- needed a "safety song" to reassure people when they buy bags o' glass or explosive tinderboxes on wheels. CCC input parameters into its music-simulating application to yield "Safe and Sound." Then, it generated two holograms to serve as the ostensible band, which data dictated should be a basic white guy and a hilarious wild card. "Safe and Sound" was released as a single, not for the sake of the holograms' careers (duh) or even to be promoted into a big hit, but rather for the song to become vaguely familiar prior to being used in commercials a few years later. Now, the commercials are here, and the true purpose of "Safe and Sound" is realized: To sell us plebs on our doom.

0 Comments

Robert Palmer was the puppet master of the beautiful, drugged, stylish, vacant mannequins in his video for "Addicted to Love." The song is anonymous 80s meat. The video deliberately exaggerates a misogynistic aesthetic, complementing the droning guitars and drug-pun-rich lyrics. This vacuous fascist fashion is how Robert Palmer is remembered, if at all. Speaking of remembrance, I was struck, upon Palmer's death in 2003, at how anticlimactic it was. I didn't expect his death to cause global mourning as with Frank Sinatra, George Harrison, Jerry Garcia, or even Warren Zevon, but I thought he might merit a bit more than this cursory, loveless obituary. No tears for a craven 80s schlockmeister, I concluded.

David Bowie's death in January triggered many deserved tributes. He was the greatest rock star ever.

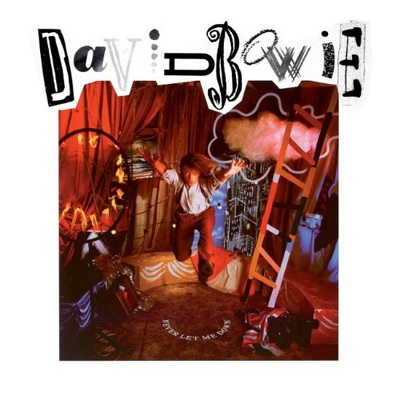

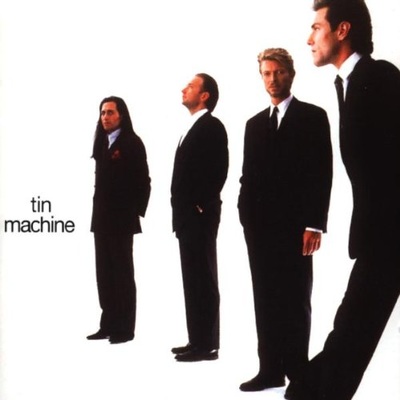

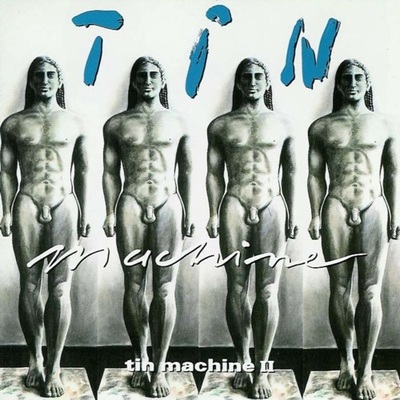

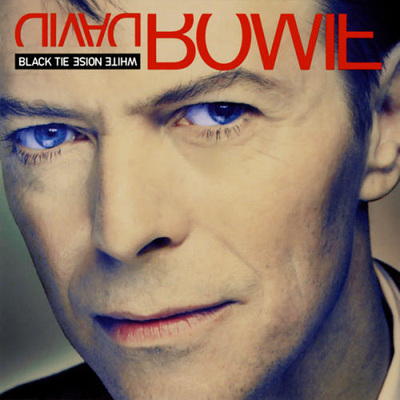

But during the 1990s (technically 1987 to 2003), he released an amazingly long and unbroken string of terrible fascist albums. It would take a perverse revisionist* -- and there were plenty in the weeks after his death -- to deny how far he fell during these years. The Cliff's Notes Bowie is this: He came on the scene in the late 1960s as a psychedelic folkie, then hit his creative stride in the early 1970s as the glam Ziggy Stardust. He soon turned to "plastic soul," the Thin White Duke persona, and mountains of cocaine. Clean by 1977, he headed to Berlin to release a trio of artsy, acclaimed albums. Then he wanted to get popular again and released a big, ominous, arena-rock album (Scary Monsters... and Super Freaks) and two popular dance-rock albums (Let's Dance and Tonight). After these commercial successes, Bowie was at a crossroads. He chose fascism.

After so many embarrassments, it was time for Bowie to finally give up, which he did. But in a happy coda, 10 years later, he released two pretty good albums, 2013's The Next Day and 2016's Blackstar. His output from 1969 to 1983 had already ensured his legacy, but these two showed he was at least capable of humor, drama, and striving -- antidotes to fascism all -- and willing to share his gifts in his waning years. *One revisionist, Jason Hartley, came up with the Advanced Genius Theory to address work exactly like Bowie's 1990s output. Per Hartley's theory, since Bowie is an acknowledged genius, it's natural that the genius present in his work would eventually exceed his audience's ability to appreciate it. The "problem," then, lies with us, not Bowie.

It's a story as old as artistic integrity: Indie rocker hits it big doing it his way and thinks he has the right to jag into something darker, label demands a more radio-friendly sound, artist balks but ultimately caves. Ryan Adams's third and Dave Matthews Band's fourth records fit the bill exactly. Adams crooned rainy-day intimacy on Heartbreaker and made a game but slightly lackluster swipe at superstardom with Gold. With Under the Table and Dreaming, Crash, and Before These Crowded Streets, DMB proved that a fervent fanbase, grassroots marketing, and great songs could overcome a lack of a genre or homerun singles. Both hit the studio in the early 2000s ready for a deep dive inward. In fact, both recorded an album's worth of despondent, spare, and uneven songs. Their respective labels were unimpressed and gently demanded that they start over: more guitars, more hooks, better work. Adams and DMB both complied. A few key differences emerge at this point, however. Adams was petulant and enraged. He thought his initial set of mopey songs, which would later be released as Love as Hell, was genius, and scoffed at his label's demand for a more rock sound. As a middle finger to his label (which, ironically, was the artist-friendly Lost Highway), he wrote and recorded a deliberately souped-up, meaningless album. Highlights (or lowlights) included a U2 parody, replete with glistening Edge-like guitar arpeggios and mock-profound lyrics ("So Alive," released as the first single); a song that sounds like an outtake from 1974 ("1974"), half an album's worth of post-grunge filler ("Burning Photographs" and "Luminol," to name two), and a song with the following lyrics: "I'm as lonely as boys / I'm as lonely as boys / I'm as lonely as monkeys taught to destroy / Anything they learn to enjoy" ("Boys"). The label released it, critics reacted with confusion or outright anger, and Adams disowned it. Ryan Adams and Dave Matthews are completely different characters, of course, and Dave's reaction matches his more earnest personality. He was just as upset as his label was that the dark, sleepy set his band recorded with producer Steve Lillywhite didn't work. So he barreled through a marathon writing and recording session with the help of pop svengali Glen Ballard, coming up with heavy, hooky songs just like Adams did. Matthews, however, wasn't joking. His band's Everyday record was just as slick, greasy, and empty as Rock N Roll, but DMB proclaimed it their best work. They cheerfully slogged through embarrassing music videos and awkwardly tried to slip dumb, offensive trifles like "I Did It" into concerts alongside their challenging and emotional repertoire. Only after fans had discarded Everyday in favor of the Lillywhite sessions did the band sheepishly and belatedly semi-disown the record.  Which is the more fascist effort? Adams consciously endeavored to create a fascist artifact of "label rock," and he certainly succeeded. But you could certainly make the argument that his record, while fascist on his face, was an arch anti-fascist commentary. Everyday doesn't get to hide within the safe cocoon of snideness; the label said jump, and Dave said how high. When you think of the way DMB repurposed the tropes of their old, organic work -- the crunchy Rolling Stone cover, the crowd-chant of "Everyday" -- you're left with the inescapable sense of dread that characterizes all the best fascist music. So while Rock N Roll hits more fascist notes in the absence of context, when you do consider context, as you must, Everyday is the more fascist record. Full disclosure: Rock N Roll is one of my favorite records by any artist ever. I like Everyday a lot, too. Let's start with a little background on what ZZ Top was. If you're like I was as a kid, you probably only know ZZ Top as the guys with the beards who are listed last on jukeboxes. Their legacy is oddly null, which is surprising because their history is rich and, for one world-beating period in the mid-1980s, undeniably fascist.

Against this background, 1983's Eliminator was a revelation. They kept their heavy guitars, but organic drums were replaced by clinical synthesized blips, the songs got a glittery production sheen, and these middle-aged bearded guys started showing up on a nascent MTV as mysterious kingpins, singing about cocaine and Great Danes and often bestowing magic on young people with the help of a 1930s Ford (the "Eliminator" shown on the album cover).

In addition to the musical coup d'etat, some fascist commendation is in order for the album titles: Eliminator, Afterburner, and Recycler. Generations have been satisfied with the explanation for the Eliminator album title being, "It's the name of the car." As explanations go, that's insane. The car didn't have to be on the cover. Even granting the cover to the car, it doesn't necessarily follow that they'd name the album after the car. Cars have names? Why were they messing with a 1930s Ford at all? Did it have significance other than being the magic car from the videos? Did they conceive of the videos before coming out with the album? Was the car, in fact, magic? So many questions, with the only clear fact being that the conventional explanation is no explanation at all. "Eliminator" was a consciously chosen word, and it's about the most fascist one they could have chosen. "Afterburner," I guess, is how the machine continues to operate even though freedom fighters have unplugged it. And "Recycler" is a similarly inscrutable title, eliciting a forboding, metallic sense of unstoppable automation and repetition. (It helps that the members of ZZ Top are presented on the album cover as shadowy thugs.) Again, ZZ Top consciously selected each of these titles. No explanation seems to make sense except their desire to further their own fascist narrative. Which they did, to their lasting credit.

|

What is fascist music?In Dave Marsh's 1979 review of Queen's Jazz, he wrote, "Indeed, Queen may be the first truly fascist rock band." No other word so neatly expresses supremacy of the powerful and devaluation of the individual. Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed